27 May 2021

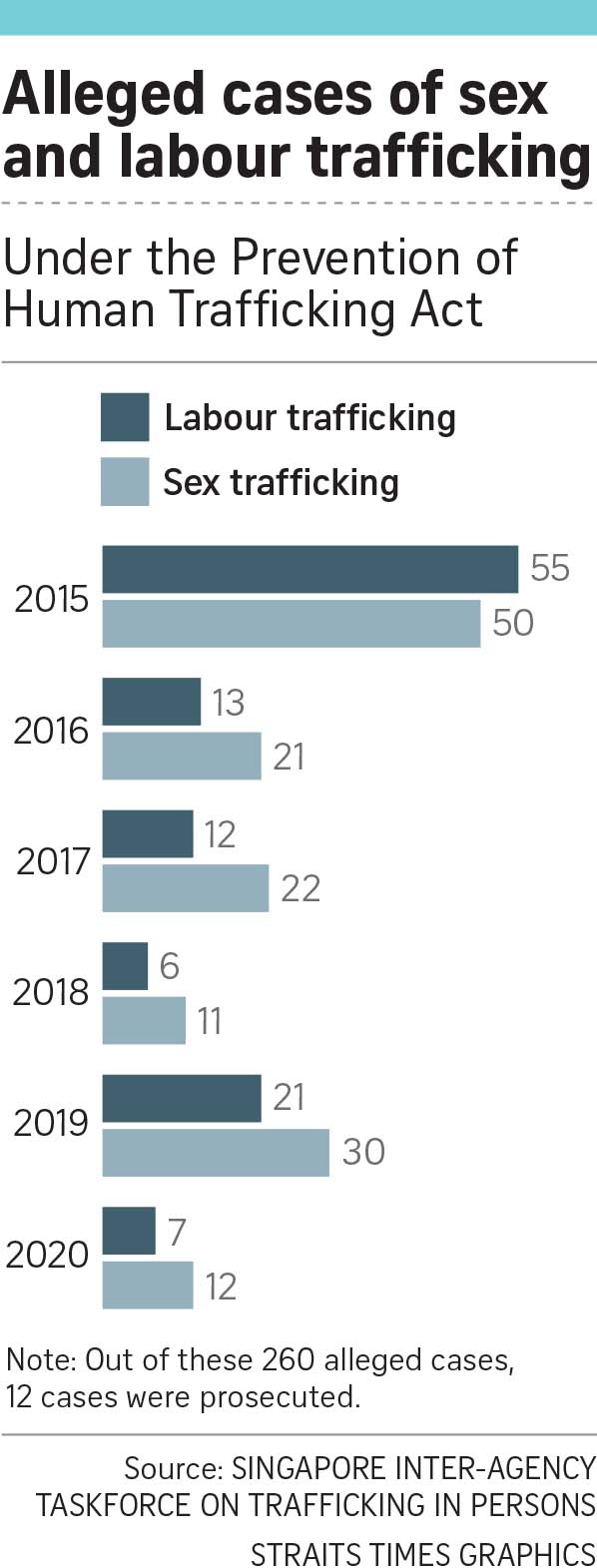

Since 2015, 260 alleged cases of sex and labour trafficking have been investigated

The conviction of Jonathan Ching on Tuesday under the Prevention of Human Trafficking Act (PHTA) cast a spotlight on the issue of human trafficking in Singapore – and how crimes that do not entail people being smuggled across the country’s borders can fall under this Act.

Ching, 25, recruited a 13-year-old girl here on Instagram in March 2018, promising her fast cash for performing sexual acts on another man, Mohammed Ayub P. N. Shahul Hameed, 30.

Under the PHTA, recruiting a child below 18 for the purpose of exploitation – whether in Singapore or elsewhere – is an offence.

Human trafficking offences can carry higher penalties than crimes related to prostitution.

First-time offenders of human trafficking under the PHTA can be fined up to $100,000, jailed for up to 10 years, and be given up to six strokes of the cane.

Offences against women and girls relating to prostitution carry a punishment of up to seven years’ jail and a fine of up to $100,000 under the Women’s Charter.

Since the PHTA was enacted in 2015, the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) and the police have investigated 260 cases of alleged sex and labour trafficking to date, Minister for Home Affairs and Law K. Shanmugam told Parliament on May 10.

Of these, six sex trafficking cases have ended in convictions and another one was before the court at the time.

There were 12 alleged sex trafficking cases last year, compared with 30 in 2019, according to data from the Singapore Inter-Agency Taskforce on Trafficking in Persons. It is unclear if this dip can be attributed to the Covid-19 pandemic, the task force said.

In South-east Asia – described by international organisations as a hotbed of human trafficking – only Singapore and the Philippines are ranked Tier 1.

Front-line service and enforcement officers from the police, MOM and the Immigration and Checkpoints Authority are trained to detect potential cases of human trafficking. This includes noticing travellers’ body language, baggage, belongings and documents, Singapore’s task force told The Straits Times.

Within Singapore’s borders, officers are also trained to spot signs of restriction of movement or confinement, the withholding of documents such as passports, and signs of coercion, deception and physical harm. Officers are also taught to “manage the victims in a sensitive manner”.

International partners such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and Interpol have conducted such training and seminars.

Mr Shanmugam said the Government supports and funds NGOs that provide victim support services such as shelter, sustenance and counselling.

The pandemic has made providing support more challenging, said Hagar Singapore, an NGO that has had to move counselling online.

Hagar executive director Michael Chiam said the pandemic has also impacted the poor and the vulnerable more greatly, and exposed inequalities more starkly.

“People are becoming more vulnerable to exploitative employment. Struggling to make ends meet, vulnerable persons turn to risky job offers even though the terms are unfair – which is very worrying,” he said.

Original Parliamentary question and response by Mr K Shanmugam, Minister for Home Affairs and Minister for Law

Original Parliamentary question and response by Mr K Shanmugam, Minister for Home Affairs and Minister for Law

Help us transform lives

Join HAGAR to empower survivors of trafficking and abuse to start a new life.

Help us transform lives

Join HAGAR to empower survivors of trafficking and abuse to start a new life.

Help us transform lives

Join HAGAR to empower survivors of trafficking and abuse to start a new life.